“We’re not using all the tools we have available to us, and it doesn’t make sense.”

Lilly Canada | March 30, 2021

Tags | Policy

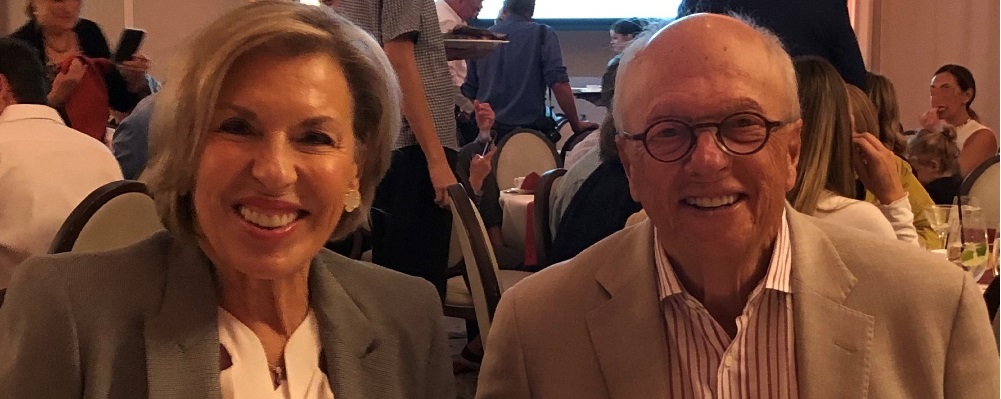

John Tavel is a retired lawyer who lives in Ottawa. Despite following all the guidelines for avoiding infection, he contracted COVID-19. It started with fatigue, which is unusual for John, and it progressed to a low-grade fever and a terrible headache. He’s 80 years old, so while he’s healthy and active, his age puts him at higher risk of progressing to severe illness from COVID-19.

His symptoms got worse, so he put on a mask and went to see his doctor. At that time, his wife, Sunny and his children asked the physician if John could receive a monoclonal antibody treatment, like what was given to the president of the United States. John’s doctor followed up with infectious disease specialists in Ottawa and Toronto, and both indicated that this treatment was currently not authorized for use in Canada. However, an antibody therapy had been authorized for use in Canada more than a month prior, and Canada had already received its first shipments at the time of John Tavel’s diagnosis.

John’s daughter Robyn says, “medicine is about following the science and the data, and there seems to be a real brick wall between the two countries when it comes to how physicians share research and information. Living in the US, I was seeing great success and experience with antibody treatments that were keeping patients out of hospital and accelerating recovery times, and the Canadian medical system didn't seem to be aware of these treatments.”

In the US, hundreds of thousands of people have been treated with monoclonal antibodies. Here in Canada, health agencies are employing an abundance of caution. In response to questions on the subject, some health experts explain their decision against adopting antibodies by saying “we are a little bit tipped toward [having identified] the people that should use this drug, but the trials were not 100%.”

John was sent home from the hospital with advice to bring his fever down with acetaminophen, but his symptoms worsened. When his fever climbed above 103˚F, Sunny called 911. John was taken to the hospital by ambulance, given oral antibiotics for pneumonia and IV fluids for dehydration, and then he was sent back home.

John says, “I was checking my temperature so frequently that the battery ran out on the thermometer. It was a stubborn fever, but I was able to attend my granddaughter’s virtual bat mitzvah, before going back to the hospital for a second time.” During his second visit, John was admitted, treated with dexamethasone, and he was kept overnight for observation.

According to Dr. David Kessler, who is serving as the head of the program to accelerate the development of COVID-19 vaccines and other treatments in the United States, 70% of people who are at high risk of progression and receive antibody treatments avoid hospitalization.

Robyn asks, “why isn't the healthcare system using these treatments if we have them here in Canada to use? If it’s the cost—my dad had to go to the hospital on two separate occasions to receive support and ineffective treatments. Clearly that’s more expensive, and it feels as if we’re not using all the tools that we have available to us.”

She says, “It just doesn’t make sense.”