Lilly's Black History Pioneers

January 31, 2022 Posted by: Eli Lilly and Company

When President Harry Truman signed an executive order to desegregate the United States armed services in 1948, it opened the door for racial integration and equality and is considered the beginning of the Civil Rights movement.

In 1948, after he became president of Lilly, J.K. Lilly Jr., issued a policy that required Lilly's black workforce to reflect the percentage of blacks in the city of Indianapolis and "that there should be no discrimination in matters of wages, treatment, or other personal considerations." Cafeterias, employee lounges, and restrooms were desegregated in 1951.

Diversity, equity, and inclusion are critical to our reputation, business, and values. Our employees are our strength, and we celebrate the contributions of our pioneering employees.

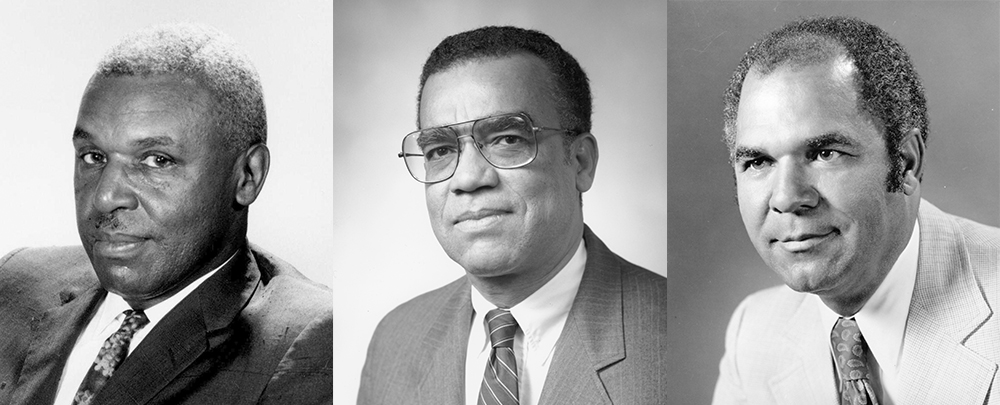

Clifford Wilson Sr. (pictured left) began his career at Lilly in 1929 as a window washer. Wilson was transferred to the Lilly Clinic at the City Hospital (Wishard/Eskenazi), where he worked as a laboratory technician. The staff was aware of his keen interest in lab work and his ability to tinker with things to improve on them. As research problems developed, the team told Wilson what they wanted to accomplish, and he would build a contraption to fit the bill. Wilson constructed a profusion instrument or artificial heart. He and an associate invented an electrical recording rotometer, a device for metering and recording blood flow, used for the diagnosis of hypertension. Wilson also created a filter for rapid filtration of plasma. Wilson's last position at Lilly was as a supervisor in Physiology in the Laboratory for Clinical Research until he retired in 1972. He died in 2002.

Standiford Cox (pictured center) had a thirty-two-plus-year career with Eli Lilly and Company. During his first couple years of employment, he obtained a master's degree in organic chemistry from Butler University's night school program. He began at Lilly as the first black chemist in 1957. Cox's first position dealt with synthesizing organic compounds. One such compound was glutamine, an amino acid vital to the production of vaccines. In 1958, at the age of 23, Cox developed a new synthetic process that allowed Lilly to produce the Salk polio vaccine at one-tenth the former cost. In 1981, he was promoted to Director of Production Control Laboratories, the position from which he retired in 1989. Cox died in 1991. Cox was a generous advocate for the preservation of African American heritage sites.

In 1962 Hayward Campbell Jr., Ph.D. (pictured right) was hired as senior bacteriologist at Lilly. His department was responsible for new testing procedures for biological products and improving the old tests. Within a year of joining Lilly, he was appointed head of biological assay. He received promotions every couple of years after that, culminating with his 1976 appointment as a vice president of Lilly Research Laboratories. Campbell was the first African American to assume such a senior rank within the company. Campbell's life was cut short by cancer in 1978 at the age of 44. He was involved in many Indianapolis civic and philanthropic organizations.